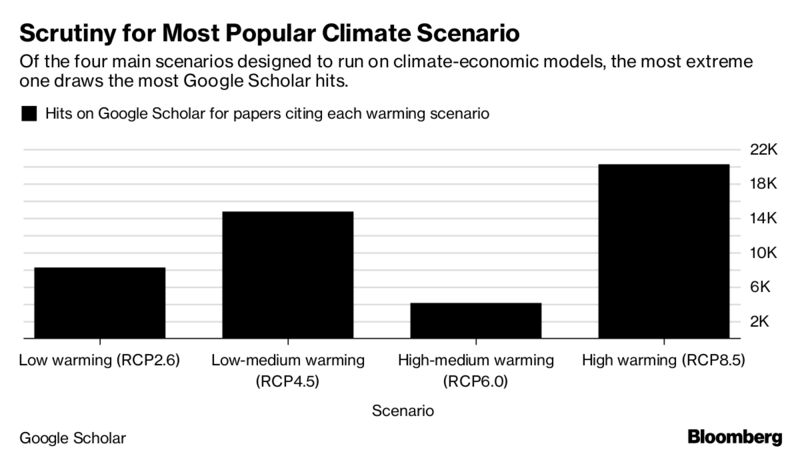

There are some 20,000 research papers listed on Google Scholar, a search engine for academics, that mention the worst-case scenario for climate change, one where an overpopulated, technology-poor world digs up all the coal it can find. Basically, it’s the most cataclysmic estimate of global warming.

This scenario is important to scientists. It focuses minds on the unthinkable and how to avoid it. According to a provocative new analysis from the University of British Columbia, it’s also wrong.

This is good news. The researchers contend that current goals of reducing coal, oil and gas consumption may be closer than we think, thus allowing us to set the bar even higher in our efforts to reduce pollution. The bad news is that this is good news in the way a destabilizing climate-shift is preferable to planetary extinction: We are still in a lot of trouble. Nevertheless, if the study is verified by other scientists and catches a wave into the realm of policy makers, it could help accelerate initiatives to arrest global warming.

The basic issue has to do with coal. Quite simply, the more we burn, the faster we destroy the atmosphere. The darkest scenario assumes much more coal burning will take place in this century than is likely to happen, according to the study’s authors. Their first paper, published in May, made it seem like the only people who see more coal use than the Trump administration are climate-scenario designers. For example, the most extreme worst-case storyline assumes that by 2100 coal would grow to 94 percent of the world energy supply. In 2015, that figure was about 28 percent.

The worst-case scenario is one of four siblings. Their names, from bad to worst, are RCP2.6, RCP4.5, RCP6.0 and RCP8.5. They were introduced in 2011 as a way for researchers running different climate-economic models to do comparable studies regarding how high greenhouse gas concentrations might rise by 2100.

These four storylines range from a 2100 in which aggressive global climate policy leads to low warming, to one in which humanity digs up and burns anything that’ll catch fire.

One big problem with the amount of coal burning assumed by RCP8.5 is that there’s probably not enough extractable coal to make the scenario possible. “We don’t think it’s going to happen,” said Justin Ritchie, lead author of the University of British Columbia study and a Ph.D. candidate. “That’s extremely unlikely and also inconsistent with every year since the late 19th century.”

RCP8.5, the authors said, fails to match up with long-term trends in world energy use. The amount of greenhouse gases emitted as a result of using energy—called the carbon intensity of energy—has been slipping for decades. Burning oil produces less carbon dioxide molecule for molecule than burning coal. Burning natural gas produces much less carbon than burning oil, and renewables such as solar and wind burn nothing at all.

The drop in carbon intensity is likely to continue as coal use peaks, which may happen in the next 10 years, according to the 2017 BP Energy Outlook. Ritchie and his co-author, Professor Hadi Dowlatabadi of the university’s Institute for Resources, Environment and Sustainability, suggest that climate scenarios should be adjusted to capture this “passive decarbonization.” Instead, 210 scenarios used in the latest report by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change projected the reverse: a “re-carbonization,” as coal’s influence overpowers much-reduced emissions from oil and gas.As national and state governments enact or update laws designed to lower emissions, policymakers rely on our evolving understanding of what’s happening to the world. If Ritchie and Dowlatabadi are right, and the very worst probabilities aren’t probable, then policymakers can set tighter goals at the same cost. By assuming that humanity, if left unchecked, would burn a lot more coal in the future, RCP8.5 may have wrongly limited the goals in our efforts to cut back.

The 2015 Paris Agreement called for limiting warming to from 1.5 degrees to 2 degrees Celsius (3.6 degrees Fahrenheit). Global average temperatures have already risen almost 1C in the past century. The 1.5C goal may already be impossible, and 2C would require major emissions reductions and, later this century, technological advances to pull enough carbon out of the air.

The disconnect between the historical decarbonization trend and the demands of RCP8.5 shed light on the often-ignored foundation of the world’s climate goals: the baseline. Paying attention to climate goals without studying optimal baselines is like watching the end of a marathon without knowing where or when it started.

“We worry if the 2C pathway is feasible, but we need to apply the same thinking and logic to baseline scenarios,” said Glen Peters, research director of the Center for International Climate Research in Oslo. Peters’s group is working to make climate-research scenarios and modeling more accessible to investors. Noah Kaufman, a research scholar at Columbia University’s Center on Global Energy Policy, agreed that goals receive vastly more attention than observed baselines, when both are actually important parts of the same story. “There hasn’t been much push toward getting these scenarios right,” he said.

Researchers run hundreds of scenarios to cover the breadth of possibilities the future may hold. For a while—when China was really coaling up a few years back—some thought the worst case looked like the coming future. Those concerns were parried by others, who pointed out that short-term pollution trends don’t mean a long-term commitment, said Detlef van Vuuren, senior researcher at the Netherlands Environmental Assessment Agency and lead author of a 2011 overview of the RCPs.

He said that just because something has become unlikely doesn’t mean it’s impossible, and given the stakes of climate change, it’s best to be thorough. There could be a coal resurgence, or methane from melting permafrost could supersize emissions, for example. “But decreasing renewable energy costs and emerging climate policy would be reasons to” expect a less calamitous outlook, van Vuuren said.

Bas van Ruijven, a senior research scholar at the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis, outside Vienna, said the new paper may not be as disruptive as its authors think. He noted even they concede that steps have been taken to improve the accuracy of the RCPs. A new generation of scenarios already harmonize better with existing trends. Three of them even show continued decarbonization—and not a return to the coal bonanza, he said.

“The community is actually already producing ‘better’ baseline scenarios that build upon recent developments in the energy sector,” including shale gas and renewables, van Ruijven said.